Years ago I simulated a pendulum for the site that was originally at this domain. I, not knowing better, used Newtonian mechanics; modelling all the forces applied to the bob, and then a very primitive forward-difference method to propagate the system in time. This worked better than you would think, in the end the pendulum looked pretty good. The code was messy, though. I had to constantly bump the bob back into a fixed radius of the anchor, since errors (floating point, forward-difference approximation) would cause the bar connecting them to telescope outwards.

Effectively, these problems were caused by ascribing a degree of freedom to the system that didn’t really exist. I would have been smarter to have only propagated the x-coordinate, and calculated the y-coordinate with the constraint imposed by the bar (although obviously the 2-valuedness of the constraint creates more problems with this). The obvious extension is to implement a double pendulum, and indeed, this is what I wanted to do. That idea, though, exposed the more fundamental problem with my approach. Calculating every force in the system for both bobs was a significantly more complicated endeavour, and I wasn’t sure that I even knew how to calculate the tension in the second bar in theory. So I did what I do best, and gave up with no resistance.

The way of the Lagrangian

Enter Lagrangian mechanics. It’s sick, in as much as an alternative formulation of classical mechanics can be. The main reasons I like it:

-

Lagrangian mechanics allows the use of

generalised coordinates. While it’s true that you can always switch the

coordinate system you use to do Newtonian mechanics, this normally comes with

some awkward factors, and still isn’t quite as flexible. In the case of the

double pendulum, it might make much more sense to use polar coordinates, with

the origin at the anchor. This works great for the first pendulum (although,

mind you, still creates a redundant degree of freedom), but makes much less

sense for the second, for which the natural “origin” is actually the first bob.

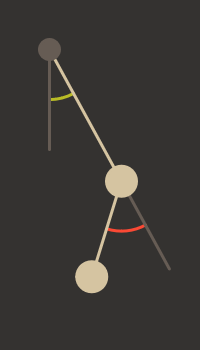

The generalised coordinates I’ll use moving forwards are \( \theta \) and \(

\phi \). Two angles which are shown opposite (\( \theta \) in green, \(

\phi \) in red). These two angles (along with their first derivatives) can

completely, uniquely, and minimally specify any state of the system.

Lagrangian mechanics allows the use of

generalised coordinates. While it’s true that you can always switch the

coordinate system you use to do Newtonian mechanics, this normally comes with

some awkward factors, and still isn’t quite as flexible. In the case of the

double pendulum, it might make much more sense to use polar coordinates, with

the origin at the anchor. This works great for the first pendulum (although,

mind you, still creates a redundant degree of freedom), but makes much less

sense for the second, for which the natural “origin” is actually the first bob.

The generalised coordinates I’ll use moving forwards are \( \theta \) and \(

\phi \). Two angles which are shown opposite (\( \theta \) in green, \(

\phi \) in red). These two angles (along with their first derivatives) can

completely, uniquely, and minimally specify any state of the system. -

All of Newtonian mechanics can be derived from Lagrangian mechanics, but not vice versa. In that sense, Newtonian mechanics is actually a specific case of the much more elegant and general Lagrangian theory. Really Lagrangian mechanics only relies on 1 axiom: the principle of least action. This, in comparison with Newtonian mechanics’

32 laws. -

Lagrangian mechanics “feels” more fundamental to me. Obviously, this is pretty tied in to the last point, and more than a little subjective. I think it is because the principle of least action arises from quantum mechanics in a beautiful, slightly unexpected way. By contrast, the easiest way to reach the famed

32 laws (without using Lagrangian mechanics) is the correspondence principle (I think), which, let’s face it, is cheating. -

Lagrangian mechanics is actually much easier. I really don’t know why it isn’t normally taught to younger students. I wasted so much time farting about, trying to determine where and how forces would act in different frames and setups. Controversially, maybe, I just don’t think the concept of a force is very intuitive, in any sense other than it being something that motivates acceleration. Half the time they don’t even change the speed of objects which is beyond confusing. Any system, through the lens of Lagrangian mechanics, is as simple as finding the kinetic and potential energies (assuming it is conservative). It’s hard to overstate the massive simplification that represents. No longer do you have to remember the equations for forces, and potentials in multiple frames and try to tie them all together in a way that makes sense. Now, you just have to calculate the total kinetic and potential energies of a system as function of position, velocity, and time and you’re away. The rest of the work is just mindless machinery. Sure, least action isn’t necessarily intuitive, but it is, at least, easy.

That settles it, I think we can all agree that there’s no point ever using \(F = ma \) again.

Getting that motion equated

Well the promise is that if we can work out the kinetic and potential energies for the double pendulum we will have solved it, so what are they? Let’s start with the kinetic energy.

Kinetic energy

The kinetic energy of bob 1 (the one connected directly to the anchor), is easy: $$ T_1 = \frac{1}{2} m_1 {l_1}^{2} {\dot{\theta}}^2 $$ where \( m_1 \) and \( l_1 \) are the bob’s mass and the length of the bar connecting it to the anchor, respectively; and \( \dot{y} = \frac{d\theta}{dt} \). In case it’s not clear where this formula came from, there are two ways to look at it. From a rotational mechanics point of view, it’s \( T = \frac{1}{2}I \omega^2 \), where \( I \) is the moment of inertia, and \( \omega \) is the rate of rotation. Alternatively, it’s the classic \( T = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 \) when you consider that \( v = l_1\dot{\theta} \).

The kinetic energy of bob 2 is a little more involved. I’m convinced that the easiest way to think about it is to decompose the bob’s velocity along axes parallel and perpendicular to bar 1: $$ \begin{bmatrix} l_1 \dot{\theta} + l_2 \dot{\phi} \cos\phi \cr l_2 \dot{\phi} \sin\phi \end{bmatrix} $$ which gives $$ T_2 = \frac{1}{2} m_2 \left[\left(l_1 \dot{\theta} + l_2 \dot{\phi} \cos\phi\right)^{2} + \left(l_2 \dot{\phi} \sin\phi\right)^{2}\right] $$

Of course the total is just the sum of these. $$ T = T_1 + T_2 $$

Potential energy

The potential energy is much less complicated, it only arises from gravity (these pendulums aren’t forced in any way). For convenience, I’m defining \( V = 0 \) for a mass in this field as being at the same altitude as the anchor. So for bob 1 $$ V_1 = -m_1 g l_1 \cos\theta $$ and for bob 2 $$ V_2 = -m_2 g \left(l_1 \cos\theta + l_2 \cos\left(\theta + \phi\right)\right) $$ Once again, the total is $$ V = V_1 + V_2 $$

With these we can form the Lagrangian, \( \mathcal{L} \), which for a conservative system is \( T - V \) for reasons I won’t go into here. $$ \mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} m_1 {l_1}^{2} {\dot{\theta}}^2 + \frac{1}{2} m_2 \left[\left(l_1 \dot{\theta} + l_2 \dot{\phi} \cos\phi\right)^{2} + \left(l_2 \dot{\phi} \sin\phi\right)^{2}\right] \\+ m_1 g l_1 \cos\theta + m_2 g \left(l_1 \cos\theta + l_2 \cos\left(\theta + \phi\right)\right) $$ Amazingly, to me at least, this one equation encodes all the motion of the system. Of course, just looking at it, it’s hard to see how you’d divine anything about how the bobs will move. I’ll skip another involved derivation and instead present the Euler-Lagrange equation, which is the machinery we need to turn \( \mathcal{L} \) into useful equations of motion: $$ \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial q} = \frac{d}{dt}\left[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{q}}\right] $$ where \( q \) represents any one of our generalised coordinates. This means that we will have exactly as many equations of motion as we do coordinates, which is convenient as it means that we should have enough equations to solve for all of them.

Finally, let’s plug \( \mathcal{L} \) in to get the equation of motion for \( \theta \): $$ \begin{align} -\left(m_1 + m_2 \right) g l_1 \sin\theta &\phantom{}\\ -m_2 g l_2 \sin\left(\theta + \phi \right) &=\left(m_1 + m_2 \right) {l_1}^{2} \ddot{\theta} \\ &\phantom{/,/,} +m_2 l_1 l_2 \left(\ddot{\phi} \cos\phi - \dot{\phi}^2 \sin{\phi}\right) \end{align} $$ and \( \phi \): $$ \begin{align} -m_2 l_2 \dot{\phi} \sin\phi \left(l_1 \dot{\theta} + l_2 \dot{\phi} \cos\phi \right) &\phantom{}\\ +\frac{1}{2} m_2 {l_2}^{2} \dot{\phi}^2 \sin\left(2\phi\right) &\phantom{}\\ -m_2 g l_2 \sin\left(\theta + \phi \right) &= -m_2 l_2 \dot{\phi} \sin\phi \left(l_1 \dot{\theta} + l_2 \dot{\phi} \cos\phi \right) \\ &\phantom{/,/,} +m_2 l_2 \cos\phi \left(l_1 \ddot{\theta} + l_2 \ddot{\phi} \cos\phi - l_2 \dot{\phi}^2 \sin\phi \right) \\ &\phantom{/,/,} +m_2 {l_2}^{2} {\sin}^2\phi \ddot{\phi} \\ &\phantom{/,/,} +m_2 {l_2}^{2} \dot{\phi}^2 \sin\left(2\phi\right) \end{align} $$ It’s at this moment that you might consider abandoning your career in Lagrangian mechanics. Not only are these differential equations disgustingly long, they’re intricately coupled, and not linear. You’d be right to panic. Luckily though, we can outsource all of that hard work to silicon. The challenge then becomes correctly inputting these equations which is far more achievable, in my mind at least (even so, it did take me several tries to convert these to code). Not having to worry about a closed form solution is great and all, but it’s still unclear how we’d get a computer to solve this system anyway.

Runge-Kutta, I hardly know her

The method I ended up with is 4th-order Runge-Kutta, or RK4, which can solve systems of the form $$ \frac{d\vec{u}}{dt} = \vec{f}\left(\vec{u}, t\right) $$ for some state vector \( \vec{u} \). This obviously presents a problem, as our problem currently looks like $$ \frac{d^2\vec{u}}{dt} = \vec{f}\left(\frac{d\vec{u}}{dt}, \vec{u}, t\right) $$ Awkward! But thank goodness, it turns out you can always rewrite second order differential equations that are linear in \( \ddot{\vec{u}} \) as a set of twice as many first order equations. To do this we define \( \alpha \) and \( \beta \). $$ \frac{d\theta}{dt} = \alpha, \frac{d\phi}{dt} = \beta $$ If you squint, you might notice that we already have two of our four first order equations right there. Amazingly simple, I’m sure the other two will be just as compact (definitely not foreshadowing).

Effectively the problem has become just solving simultaneous equations for \( \dot{\alpha}( = \ddot{\theta} )\), and \( \dot{\beta}( = \ddot{\phi}) \). There’s a lot of variables and parameters knocking about that are giving me an uneasy feeling, so we can rewrite the equations of motion above as $$ \begin{align} A\dot{\alpha} + B\dot{\beta} &= C\\ A’\dot{\alpha} + B’\dot{\beta} &= C' \end{align} $$ which looks really simple as long as you ignore that $$ \begin{align} C &= -\left(m_1 + m_2\right) g l_1 \sin\theta\\ &\phantom{/,/,}-m_2 g l_2 \sin\left(\theta + \phi\right)\\ &\phantom{/,/,}+m_2 l_1 l_2 \beta^2 \sin\phi\\[0.5ex] A &= \left(m_1 + m_2 \right) {l_1}^2\\[0.5ex] B &= m_2 l_1 l_2 \cos\phi\\[0.5ex] C’ &= -m_2 g l_2 \sin\left(\theta + \phi \right)\\[0.5ex] A’ &= m_2 l_1 l_2 \cos\phi = B\\[0.5ex] B’ &= m_2 {l_2}^2 \end{align} $$ which is great because we totally can ignore it, rewrite those as a matrix equation: $$ \begin{bmatrix} A & B\\ A’ & B' \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} \dot{\alpha}\\ \dot{\beta} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} C\\ C' \end{bmatrix} $$ and solve it: $$ \begin{bmatrix} \dot{\alpha}\\ \dot{\beta} \end{bmatrix} = \frac{1}{AB’ - BA’} \begin{bmatrix} B’ & -B\\ -A’ & A \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} C\\ C' \end{bmatrix} $$ which leaves us with the other two equations, to complete our set: $$ \frac{d}{dt} \begin{bmatrix} \theta\\ \phi\\ \alpha\\ \beta \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \alpha\\ \beta\\ \frac{B’C - BC’}{AB’ - BA’}\\ \frac{AC’ - A’C}{AB’ - BA’} \end{bmatrix} $$

RK4 is a very slightly more complicated version of the Euler method, which uses the forward-difference approximation: $$ \dot{u}(t) = \frac{u(t + \Delta t) - u(t)}{\Delta t} $$ which can be simply rearranged to the method itself: $$ u(t + \Delta t) = u(t) + \Delta t f(u, t) $$ because \( f(u, t) \) is the expression for the derivative at some time and state. The limiting factor for this method is how accurate the forward-difference approximation is, or more specifically, how inaccurate it is. RK4’s strength is producing a much better approximation to the average derivative over a step, without over-complicating the method: $$ \vec{u}(t + \Delta t) = \vec{u}(t) + \frac{1}{6} \Delta t (k_1 + 2k_2 + 2k_3 + k_4)\\[3ex] \begin{align} \vec{k}_1 &= \vec{f}\left(t, \vec{u}\right)\\ \vec{k}_2 &= \vec{f}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}, \vec{u} + \frac{\Delta t}{2}\vec{k}_1\right)\\ \vec{k}_3 &= \vec{f}\left(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}, \vec{u} + \frac{\Delta t}{2} \vec{k}_2\right)\\ \vec{k}_4 &= \vec{f}\left(t + \Delta t, \vec{u} + \Delta t \vec{k}_3\right) \end{align} $$

And that’s pretty much it. I implemented RK4 with the set of first order ODEs we derived and voilà, the finished product. It’s pretty buggy, I’m assuming because sometimes RK4 diverges for certain combinations of parameters, but works way better than I expected it to.

Finishing statements

I just wanted to mention that it obviously can be intimidating to look at a page

of polished algebra like this, but what you don’t see is that this whole process

took me 3 days to work out. I had a rough game plan at the beginning, but

suffered a few false starts, not being able to actually find the right kinetic

energy of the system. There were hours of debugging, mysterious NaNs, systems

that seemed to be working but just didn’t quite move “right” before I ended up

with the method above. The whole thing is undeniably an improvement on my last

attempt, but if I hadn’t learnt about these methods during my degree I wouldn’t

have been able to do this at all, which brings me on to my final point.

This still isn’t a good way to do the problem. Other double pendulum simulations online don’t have the same bugs as mine, and there are likely libraries that would have made large parts of the process much easier and more stable. Despite that, I’m glad I stuck with it, and I’m glad I tried the pendulum before I knew any of this stuff. It feels good and is much more rewarding to implement everything by yourself. I’d really recommend it, in general.

Finally, a note on Lagrangian mechanics. There’s something kind of strange and maybe a bit disturbing about seeing “real-looking” motion emerge from the series of inscrutable equations above. Normally when I model a system, it comes together in pieces, and I can see what each force is doing. Here, there’s no such process. I worked out the equations of motion on paper, inputted them, and watched the pendulum come to life. I’m not really sure what my point is here, apart from that least action is weird, and I think it’s worth experiencing it for yourself.

Back to the other posts?